|

,

And you may find yourself Living in a shotgun shack And you may find yourself In another part of the world And you may find yourself Behind the wheel of a large automobile And you may find yourself in a beautiful house With a beautiful wife And you may ask yourself, well...How did I get here? Talking Heads From an early age we are taught to follow the rules of society very seriously. We are thrown into a predetermined set of familial, and more broadly, cultural norms that drive and define us. For most of our waken time, we act and do what we are told without question. We follow in our parent's foot steps and when we astray we are redirected back to the norm by modeling and conditioning. As children we learn about ethics and morals. We learn to internalize what is right and what is wrong and how we should act, think and behave in different situations. Even before we are born, we have a name, a demarcation that already has significance and affects who we will become. We fear making a mistake; be it getting a "D" in school, not getting into the right college, choosing the right spouse, finding the right profession, raising your kids properly or saving enough in your 401k. We live our lives propelled forward -- looking backwards only to remember where we came from, who we are, and the the ideals that guide us to who we become. Fredrick Nietzsche called it the "Herd," Martin Heidegger called it the "They," Sigmund Freud called it the "Super Ego," and Jacque Lacan called it the "the Symbolic." While these thinkers might not agree on all aspects of their philosophical presuppositions, their basic premise share a similar significance. We are born into a historical world, with a language, ideology and common sensibility. Like in a familiar game or sport, we learn the rules so well, we are able to play our assigned roles so naturally, without even a moment of hesitation. Be it the language we speak, the activities we do, the popular styles or fashion we follow, how we communicate, feel or related to others. This human "belongingness" to a collective symbolic order is best illustrated in today's obsession with social media. In today's world, the toddler, before she can master walking, knows how to surf the World Wide Web. We live in a society where we communicate by text, are always "connected" and are absorbed in 24/7 media and news. Ask any parent about the panic that occurs when you try to take a child's I Phone away. The 'Internet Of Things" has become the the iconic symbol of our generation's alienation from our own subjectivity -- a constant connectivity to avoid self-reflection. This avoidance to be with one's own self has reached epidemic proportions in our current society; as manifested in the abundance of obsessions, compulsions and addictions to drugs, social media, video games and internet pornography. For many of us, we are so absorbed living our lives we have no time to think about or question the very nature of our existence. It is only when we are jolted by a specific event or perhaps a developmental crisis, we find ourselves thrown into self reflection and ridden with existential doubt and anxiety. For many this existential crisis manifests in the form of psychological symptoms, be it panic attacks, insomnia, obsessions or compulsions, feelings of helplessness, a sense of directionless, lack of pleasure or molase. For many it is arises in the form of a mid-life crisis" or confronted by an illness or older age. In my practice, I often here people say: it felt as if one day I awoken out of a deep sleep and found myself entangled into a strange life, surrounded by people I don't know and working a meaningless job I don't like. How did I get here? is a question many people ask when we meet for the first time in my office. Why did we turn out way we did? What were the underlining reasons that caused us to be who we are? How did our lives end up the way it did? How did things turn out so different from one's expectations? Be it the 75 year old man who does not recognize his own reflection in the mirror. Where did the time go? When he looked in the mirror, the image looked more like his father than he. How about the couple who met in high school and fell in love at first sight. They were soulmates, best friends and always had each other's back. Now they find themselves married twenty years with two kids and they can barely look at each other without a conflict. A man who dreamt of fame an fortunate as a child, now counts the days to retirement and his government pension. How could a man with such promise end up working such a personally meaningless job? How does a child of the sixties, who fought for freedom and equality, find herself working for a hedge fund helping the top one percent become even wealthier? Or, the man faced with illness, question the purpose of his very existence. How did we get here? is the question that arises when the self takes a step back and reflects upon its own historical relevance. What is the purpose of my life? It is also the question that unhingers the deeper existential questions of self-identity, free will, meaninglessness and personal finitude. There is such a contradiction to the human condition. We take ourselves very seriously. Who we are, how we want to be perceived, the importance and consequence of our actions, what we look like, what we achieved, our physical health, our relationships, who we want to become. Yet, when we sit back and reflect upon the greater existential questions, our sense of self-importance can shrink to utter confusion and meaninglessness. Are we not all "bipolar" -- faced with one's own finitude, we race to achieve what we were meant to be, yet why bother, if in the grand scheme of thing, what we do does not matter. This is the human dilemma. Faced with a life crisis, getting older and an awareness of one's finitude, cracks begin to form in the foundation of one's everyday identity, purpose and significance. Panic sets in unleashing powerful waves of existential doubt and anxiety. Reflecting upon one's personal history, like a literary critic analyzing a narrative, the individual begins the process of self discovery and understanding the thematic motives upon which their lives and self identity were constructed. Personal freedom can be both a blessing and a curse. While you are free to choose your own destiny, this freedom comes with a price, an awareness of the ultimate groundlesssness of your existence. To face death, is both freeing in terms of the anxiety associated with stress of everyday decisions and concerns, yet existentially wounding and anxiety provoking when confronted with one's temporality and ultimate lack of permanency and significance. Perhaps the question "How did we get here?" naturally leads us to the question "How do we get out of here? I will let Bob Dylan have the final words. "There must be some way out of here" said the joker to the thief "There's too much confusion", I can't get no relief Businessmen, they drink my wine, plowmen dig my earth None of them along the line know what any of it is worth. "No reason to get excited", the thief he kindly spoke "There are many here among us who feel that life is but a joke But you and I, we've been through that, and this is not our fate So let us not talk falsely now, the hour is getting late". Dr. Martin H. Klein is a psychologist with offices in Fairfield and Westport CT Westport psychologists Fairfield psychologists

0 Comments

Seems like I have had these same old blues now since old time began So I went to talk my troubles to the hoodoo man I told him all about my problem, and I asked him what was wrong He said you got to live the blues, if you want to sing your song Seems like I'll always lose, you've got to suffer if you want to sing the blues David Bromberg When potential new patients call they often ask: “What is your approach to psychotherapy?” It is understandable that such a question is being raised, especially if the caller found me via a google search, rather than by visiting my website or by referral. It is not always so easy to provide a comprehensive explanation of my clinical approach within the context of a brief introductory phone call. My strategy has been to ask a lot of questions before I answer such inquires as a means of trying to figure out what exactly the person is looking for in terms of an explanation. Often times people just want simplistic answers. Do you do Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT)? Brief Focused therapy? Do you work with people who have my specific issues? How many sessions will it take to fix my problem? While brief focused treatment might be appropriate for some people, for others, a different approach might make more sense. As a seasoned psychologist I believe I have earned the right to say “I have seen it all” when it comes to clinical treatment. Yet, I can also say, that each person I have met within my 30 years of practice has been different, with a unique story and set of presenting problems. In clinical practice no two people are alike and one size does not fit all when it comes to the psychotherapy process. It might be popular — and even financially and politically motivated by some — to view psychology as a rigorous science with precise tools. Therapy, however, is an art and has more in common with spiritual pursuits and literary analysis than physics or organic chemistry. At the heart of the psychotherapy process is the relationship between the patient and the therapist, not just the tools in his bag of tricks. What is important is trust, confidentiality, empathy, understanding, insight, and motivation for change, rather than quantifiable outcomes and objective criteria. As a clinical psychologist I believe it is important to do a thorough psychological assessment and psychosocial history prior to committing to a certain approach or treatment plan. You need to understand the person and his or her unique circumstances before deciding on a clinical modality. For some, brief therapy like CBT makes sense. They are dealing with a particular symptom or behavior they want to go away. For others, however, symptoms are symbolic of something deeper, perhaps struggles with self destructive patterns, chronic feelings of depression or anxiety, or negative personality traits that are maladaptive. In these cases, focusing solely on symptom reduction would be equivalent to a fireman deciding to shut off the fire alarm rather addressing the underlining issues that are causing the fire. Symptoms can be a valuable tool both as an indicator that something is wrong as well as a motivator for personal change. Sometimes shutting off the alarm temporarily as you proceed to put out the fire makes sense, but just shutting off the alarm without doing the necessary work to resolve the underlying structural issues will more often than not lead to poor outcomes. David Bromberg, the folk singer once said “you have to suffer if you want to sing the blues.” It is my experience that sometimes you have to suffer to stop singing the blues. For it is each person’s discomfort that motivates them to call me up, ask about my philosophical approach and get the help they need to become happier, more free and confident in who they are and what they want to become. Psychotherapy is an inward journey, and the therapist is a guide on the path of change, not a scientist with a white coat, stethoscope and prescription pad. Dr. Martin Klein is a psychologist who practices in the County of Fairfield. He utilizes several treatment modalities in his practice including cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), existential psychodynamic analysis, insight oriented couples counseling, hypnotherapy, supportive client centered counseling, and action focused motivational Executive Coaching. In the realm of psychotherapy, various approaches have emerged over the years to help individuals grapple with their psychological struggles. One such approach is existential psychotherapy, a philosophical and psychological framework that delves into the fundamental questions of human existence. Rooted in the existential philosophy of thinkers like Søren Kierkegaard, Martin Heidegger, Jean-Paul Sartre, and Viktor Frankl, existential psychotherapy offers a unique perspective on understanding and addressing the challenges of life. Existentialism is not just a therapeutic technique; it's a a way of viewing human existence. At its core, it seeks to explore the profound questions of existence, meaning, and purpose. It acknowledges the anxieties and uncertainties that are inherent in human life and aims to help individuals confront these existential concerns. Key Concepts 1. Freedom and Responsibility: Existential psychotherapy emphasizes the importance of personal freedom and the responsibility that comes with it. It encourages individuals to recognize their agency in shaping their lives, even amidst challenging circumstances. 2. Death and Mortality: Confronting the reality of mortality is central to existential psychotherapy. The awareness of our limited time on Earth can prompt individuals to reflect on how they want to live and what truly matters to them. 3. Isolation and Connection: Existentialists recognize the paradox of human existence—our inherent sense of aloneness, coupled with our longing for connection. Existential psychotherapy explores how individuals can find authentic connections while respecting their unique identities. 4. Meaning and Purpose: The search for meaning is a central human endeavor. Existential psychotherapy encourages individuals to explore their values, passions, and pursuits that give life a sense of purpose and fulfillment. 5. Anxiety and Dread: Existential anxiety emerges from the tension between the desire for certainty and the reality of uncertainty. The therapy aims to help individuals navigate anxiety by embracing ambiguity and finding ways to live meaningfully despite it. 6. Authenticity: Being true to oneself is a cornerstone of existential psychotherapy. It involves examining societal norms, values, and expectations to determine what genuinely resonates with an individual's essence. Existential psychotherapy is practiced by psychologists who adopt a collaborative and exploratory approach. Rather than providing quick solutions, therapists create a space for clients to engage in deep introspection and dialogue. They assist clients in understanding their beliefs, values, fears, and aspirations, guiding them toward a more authentic and meaningful life. Benefits of existential analysis includes gaining a sense of agency and empowerment by recognizing their capacity to shape their lives, through self-reflection becoming more attuned to their emotions, desires, and values. By confronting one’s existence, a person can develop a better appreciation for the present moment and find joy in life's experiences. In other words, facing one’s own finitude — and ultimately one’s death — can challenge attachments to their everyday seriousness and transient mundane concerns. Existential psychotherapy offers a profound journey into the depths of human existence. By exploring questions of self- identity, meaning, freedom, and connection, individuals can confront their fears and anxieties, ultimately finding a path to greater authenticity and fulfillment. While not a one-size-fits-all approach, existentialism provides a unique lens through which individuals can engage with life's complexities and challenges. Dr. Martin Klein is a Westport CT psychologist who is trained in existential philosophy and psychological practice. It Was Meant To Be People often repeat proverbs as explanations as to why certain events have occurred in their lives. One saying I commonly hear is: "it was meant to be." People use this expression to account for both positive and negative events in their lives. For example, "It was meant to be that I met the man of my dreams" or "the promotion at work that I did not get was not meant to be." This saying implies that what has happened in a person's life occurred because of an external omnipotent force. These expression are stated in past tense, and is never said prior to an event as a premonition. It Happened For A Reason The proverb implies a sense of destiny -- the belief one's actions are predetermined and must have happened for a reason. In fact, some people actually say "it must have happened for a reason" rather than "it was meant to be" -- but both expressions have similar connotations. In a predetermined world, one is no longer responsible for his or her decisions. One might think she is making a choice, but in actuality she is doing what is dictated by destiny. To use an an analogy, in a world where destiny rules, one's experience of having free will is like the child's experience of being the captain of the ship on a carnival ride where the toy steering wheel has no real control of the boat that in reality travels on a fixed circular track. In other words, free will and choice are illusory. The Abandon Of Free Will Why would someone want to accept a worldview that undermines their right to self determination? Isn't personal freedom what we all strive for? From an early age are we not taught the goal of life is to achieve as much freedom as possible, be it financially, socially, at work or in one's relationships? Why would a person want their freedom taken away or diminished by some sort of authoritarian force or being? Is it possible that personal freedom is not all that it is cracked up to be? The Anxiety Of Choice Some people have a hard time making decisions. Decisions are not always easy, be it what college to go to, who to marry, where to live, how to invest, should I have kids, take this job, divorce or retire? While you often hear personal freedom is a wonderful privilege, when faced with actual choices, individuals often become psychologically paralyzed. Fear of making the wrong decision can lead to overwhelming anxiety and despair. Once the choice has been made, many individuals often doubt their decision and experience the dread associated with regret. This regret sometimes manifests itself in an obsessive like rumination: "should have" -- "could have" --"what if." Other times, it is defended against by denying the the personal responsibility for the decision. It was not my fault, or I could not have choose otherwise because it was beyond by control -- "it was meant to be." Closed Doors Paradoxically, to some individuals freedom can be experience as a limitation. To choose "A" means you did not choose "B". Decisions can be perceived as an act of eliminating options. Contrary to the popular saying, for these individuals, every time a door opens another door is closed. A closed door symbolizes one's finitude. Alexander Graham Bell said it so nicely: "When one door closes, another opens; but we often look so long and so regretfully upon the closed door that we do not see the one which has opened for us." Should Have Could Have Personal freedom can cause anxiety on many different levels. First, there is the fear of making the wrong decision. This anxiety manifests in obsessive thoughts, thinking over and over again about the pros and cons of each decision. Ironically, while it may feel like not choosing keeps open possibilities, in reality no decision is itself a choice, one that is nonproductive or forward-moving. Second, there is the anxiety associated with regret. This anxiety manifests in ruminative thoughts, the "should have" -- "could have." Coping Mechanisms and Regret Both types of anxiety are very painful and can result in despair. Many individuals develop coping mechanisms to avoid these intense negative feelings. For example, some might develop compulsions. -- repetitive rituals as a means of trying to gain a sense of control over fear of the unknown. Others might avoid the decision altogether -- perhaps alcohol or drug abuse as a means of not dealing with the question at hand. Several might deny there is even a choice -- if life is ruled by destiny -- "it was meant to be " you are not responsible for decisions, thus cannot have regrets. From experience we all know that these coping mechanisms -- be it obsessions, compulsions, avoidance or denial -- have limited abilities to defend against these fears and anxieties associated with the responsibility and pressure of self determination. Claustrophobia, Panic Attacks And The Fear of Death There is one more level of anxiety worth mentioning that is intertwined with both the fear to decide and the regret of past decisions. This anxiety is much deeper and more cumbersome than the anxieties discussed above. For the fear of limitation when pushed to its root origin brings one to the fear of one's finitude. Perhaps the claustrophobia or panic associated with a closed door is intrinsically the fear of one's mortality. The existential psychologist refer to this ultimate cause of angst as "death anxiety." But the fairy tale of "happily ever after" is perhaps a topic for another blog. Dr. Martin Klein is a clinical psychologist who specializes in the treatment of anxiety. He has offices in Westport and Fairfield CT. Westport psychologists Farifeld psychologists Copyright November 2016, Martin Klein, Ph.D. In our fast-paced modern world, the pervasive issue of insomnia, characterized by its disruptive impact on falling asleep and staying asleep, poses significant challenges to our ability to function in our everyday lives. While conventional remedies such as medication have proven effective for many, a combination of hypnosis and Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) can be an alternative approach to addressing insomnia in a more wholistic and non pharmaceutical manner.

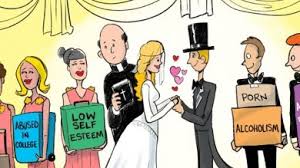

Hypnosis is a state of heightened suggestibility and focused attention. In the context of insomnia treatment, its objective lies in rewiring the subconscious mind’s entrenched negative associations with sleep while concurrently fostering deep relaxation. What distinguishes hypnosis is its capacity to delve into the roots of insomnia, bypassing the mere management of symptoms. Hypnotherapy ventures into the deep-seated issues underpinning sleeplessness, such as anxiety, racing thoughts, and counterproductive sleep-related thought patterns. By uncovering and addressing these core concerns, hypnosis endeavors to effect enduring transformations in sleep behavior. During a hypnotherapy session, a clinical psychologist adeptly guides the individual into a profound state of relaxation. Within this receptive mental space, the therapist introduces affirmative suggestions and constructive imagery specifically tailored to sleep. These carefully curated suggestions and images work synergistically to reshape the individual’s negative perception of sleep. When blended, the integration of hypnosis and CBT presents a powerful approach for the treatment of insomnia. CBT, renowned for its empirical foundation, is designed to identify and alter maladaptive thought patterns and behaviors associated with a spectrum of mental health conditions. In the sleep context, CBT takes aim at dismantling unproductive beliefs and actions linked to insomnia. The relaxation engendered by hypnosis facilitates a more fertile ground for the absorption of cognitive restructuring and behavioral modifications imparted through CBT. While the latter concentrates on dismantling negative thought patterns about sleep, hypnosis acts as a facilitator, rendering individuals more amenable to reconfiguring these thought patterns in a state of profound relaxation. Hypnotherapy becomes a haven for quelling the anxiety often intertwined with nighttime wakefulness. In parallel, CBT propounds the utility of positive affirmations as an antidote to counteract negativity. Through hypnosis sessions, these affirmations gain a newfound potency, reinforced by the profound relaxation that accompanies the hypnosis trance state. This serene mental atmosphere creates an opportune setting for the assimilation of these affirmations, gradually fostering a healthier mental outlook towards sleep. By harmonizing both conscious and subconscious elements, the combination of hypnosis and CBT provides a dynamic framework for addressing sleep difficulties comprehensively. While CBT imparts cognitive tools to recalibrate thought patterns and behaviors, hypnosis serves as a catalyst, engendering a state of relaxation that nurtures receptivity to change. Dr. Martin Klein is a clinical psychologist who practices in Westport CT as well as remotely via video conferencing. He specialized in the treatment of insomnia utilizing hypnosis and CBT. Many children are diagnosed with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), and such a diagnosis can be overwhelming for the child and his family. It can be even more stressful if your child is diagnosed with Disruptive Mood Dysregulation, which often is a disorder that accompanies ADHD. Most of us know what a child is like who has ADHD. They have a lot of energy, are impulsive, have a hard time focusing or siting still. Boys typically are diagnosed with ADHD earlier because they may be disruptive at school. Girls, on the other hand, tend to be more complicated to diagnoses because they tend to hold it together while at school, since they are so concerned about how they are perceived by others. Holding it together outside the home is not an easy task for children with ADHD. Pressure mounts, and when they are back home, in their safe environment, with the ones they love, their hair comes down, and like a shaken bottle of soda — they explode. This over the top pouring out of emotions is what professionals call Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder (DMDD). Mood Deregulation is a fairly newly diagnosis, identified just a decade ago. The cluster of symptoms associated with this disorder include low tolerance for frustration, angry outbursts, irritability, mood lability with both highs and lows, irrational fears and anxiety, including panic attacks, social phobias, obsessional thoughts and ritualistic compulsions. In the past, kids with ADHD and DMDD were put into various diagnostic categories including, Oppositional Defiant Disorder, Conduct Disorder, Personality Disorders and Mood and Anxiety Disorders. Since the relationship between ADHD and the presence of the cluster of symptoms associated with DMDD was not recognized until recently, scientific research and targeted treatment protocols - both in terms of psychopharmacology and psychotherapy - have not been clearly defined and standardized. This lack of concrete treatment modalities often results in frustration on the part of psychiatrists, psychologists, families, and of cause, the child. Psychiatrists will often try to treat the child with different medication cocktails such as stimulants, antidepressants, anti-anxiety medications and mood stabilizers. Psychologists often apply psychodynamic, cognitive behavioral, family systems and dialectical therapies as a means to help the child cope and the family endure. It is not uncommon for a family, after exhausting numerous trials of medications and psychotherapy, to feel like nothing will ever work. It is no wonder children with ADHD and DMDD often feel frustrated with treatment. They, however, are not alone. Understandably their parents often feel the same way - frustrated, hopeless, alienated from friends and family who don’t get what they are living with, depressed and angry, as well as grappling with guilt and self loathing for their negative feelings toward their child. In psychology, this parallel feelings between a child and parents is called projective identification. Projective identification is when the child, by their own negative behaviors, cause the parent to feel and then react negatively, which in turn makes the child feel rejected and bad about themselves, thus confirming the child’s feelings about him or herself, thereby reigniting his or her anger, self destructive and oppositional behaviors. I believe it is this vicious circle of projected identification that reinforces the dysfunctional family dynamics and activates the repetition of the child’s emotional turmoil. The cycle must be stopped to allow all involved to get off this wheel of pain, dysfunction and hopelessness. In order to do so, I think the first step is to understand why the child reacts as she does. I believe, from an existential perspective, it is important to truly comprehend how the child thinks, feels and experiences the world from an early age. I think it is wrong to view a child who thinks differently from the norm as “disordered.” They are not disordered, they are ordered differently than what is considered socially acceptable by today’s standards. They usually are able to think quickly, can hold multiple thoughts at the same time, see things from a different angle and have a keen sensitivity to environmental stimuli. In other words, children with ADHD often think outside the box. Thinking and behaving differently however — be it due to their impulsivity, executive function deficits, speech issues or sensitivity and creativity — can result in being ostracized by peers and even teachers, resulting in feelings of alienation for the child. I believe it is this psychological reaction to not fitting in that is at the core of the child’s mood dysregulation comorbidity. In essence, it is their keen awareness of being different that results in insecurities, anxieties and low self-esteem. Since kids with ADHD are different, they cannot always be parented in the same way a neurotypical kid is parented. Even therapeutic interventions and parenting techniques tailored specifically for ADHD children can be difficult to administer or apply consistently, which can make positive outcomes a challenge to achieve. Kids with ADHD/DMDD typically do not react well to traditional parenting techniques that rely on correction, limit-setting, and punishment (or in today’s lingo “consequences”). For example, threatening to take the child’s electronics away for bad behavior might result in worse behavior, e.g., them throwing the iPad on the floor in a fit of rage or destroying their favorite stuff animal in the midst of a temper tantrum. Rather than react to the bad behavior, the parent needs to take a step back and ask what is truly causing the child to act out, and then empathize with those feelings. Parents of children with ADHD/DMDD need to try to turn their attention from their child’s provocative, dysregulated behavior, and try to maintain a stance of empathy. For many parents, this feels like a dramatic change in the child-parent relationship, and does not feel natural. It may be antithetical to the way you were raised or how your friends are parenting their children. Parents may feel like they are letting their kids “get away” with “bad behavior”. They are subjected to well-intentioned advice from family and others that they need to learn how to say “no” to their children, not “be their friend”, and never fail to impose consequences to unacceptable behaviors. In most cases, I believe what you will find is an anxious child ridden with insecurities, fears of failure, and a deep-rooted sense of not being seen or heard, especially in a positive light. These kids get a lot negative attention due their anger and low frustration tolerance, however positive reinforcement by others is rare. This is understandable as it is hard to hug an angry porcupine, even if it is hurting and in need of love and attention. If the child is activated, rather than react to the presenting behavior, you must be attentive to what underlies and triggers the negative actions, and focus on interventions that can comfort and reduce the child’s stress. For example, if the child misbehaves, rather than punish the child, comfort the child so she feels safe and understood in terms of her needs. Over time, by soothing, his or her high level of anxiety can diminish over time. You need to know when to disengage, ignore, or distract the child. There is no science to this and it relies on trial and error. Changing the topic or pulling the child in a different direction with a different activity or line of thinking can be helpful strategic tools. Sometimes the child needs a soothing activity, so rather than pull the iPad away as a punishment, let her use it in a positive manner such as listening to music or even mindful relaxation videos. Then, provide praise for engaging in self-soothing, and successfully lowering her own arousal level. This, then teaches the child that she can indeed have control of her emotions like other people do. Improving the child’s sense of self esteem is also important. Try to focus on the child’s successes and talents rather than focus on limitations and inadequacies. Children with ADHD/DMDD tend to demand a lot of attention. Try to be attentive of their needs to be seen and heard, and react positively, rather than annoyed at their neediness. These shifts in approach are hard and take practice and patience. The good news is kids with ADHD can do better as they get older as neuronal networks mature. Older kids and adults may be more tolerant around people who are different or somewhat quirky. In fact many adults with ADHD, due to their ability to think outside the box, become the future innovators of change or models of excellence in their respective fields. The internet is filled with success stories of adults who excelled who had ADHD tendencies. For example, in sports Michael Phelps, Michael Jordon and Simone Biles, in entertainment Walt Disney and John Lennon, in technology Bill Gates and Sir Richard Branson. Perhaps as a parent of a young child with ADHD/DMDD there is light at the end of the tunnel — not the headlight of an oncoming train, but rather a fast paced shooting star. Dr. Klein is a clinical psychologist who practices in Westport CT and also works remotely via video conferencing. He works with parents who are struggling with children who have ADHD and DMDD.  Stock Market Fluctuations: Stress, Anxiety, Depression, Mood Swings As a clinical psychologist, with offices in Fairfield and Westport, I work with many individuals who are heavily invested in the stock market. A significant portion of my clientele, in fact, work for financial institutions; and their bonuses are directly tied to the performance of the markets. With so much at stake, it is no wonder that the stock market can affect how they experience their own sense of financial stability and well-being. For some, who may have lost their job or been wiped out by margin calls, a negative change in mood is understandable. For others, however, whose losses are just on paper, their sense of despair can become grossly exaggerated to the point of irrational fears about current and future prospects. These people suffer from what I call “Dow Affective Disorder.” A person with “Dow Affective Disorder” experiences bipolar swings in mood as the market moves up and down. In a bull market they feel elated and invincible. They may spend freely, even to the point of living beyond their means. Some may even use leverage or credit to achieve a persona of grandeur. In a bear market, however, these individual may fall into a deep depression; and feel stressed out to the point of irrational panic. They fear the worst— financial apocalypse. Their self-esteem goes from good to bad. They feel like a failure and their excess spending grinds to a halt. They become overwhelmed with regret. “I should have sold before it crashed, what was I thinking, how can I be so dumb.” Just as they beat themselves for not being fully invested when the market is in an uptrend, they now torture themselves for not being smart enough to divest before the downturn occurred. They fail to see their losses as temporary and fall into despair. In many instances their depressed mood causes a myopia and colors how they function and relate to others. They tend to withdraw from their families and friends and their focus narrows to only events related to the market. Rather than be with their children or complete work assignments, they are glued to the television watching a financial channel. They engage in self-defeating behaviors that intensify their sense of failure. For example, they panic and sell their holdings at a loss, which further confirms their sense of doom. They forget about the good times and feel as if their future will never be bright again. Their whole life style takes a dramatic shift — they feel poor, tighten their budget and radically reduce spending. For most people, a stock portfolio performance signifies nothing more than the monetary value of an investment vehicle at a current moment in time. These people tend not to pay attention to the daily fluctuations in the market and perhaps only glance at their investment statements on a monthly or quarterly basis. For those who suffer from Dow Affective Disorder, however, there is an irrational compulsive attachment to the stock market. They are hyper-vigilant to the split second movements of the market. They are glued to their phones and are watching the market throughout the day in real time. They are aware of how much they lost each day and continually think about their net worth. If the market spikes up they get a temporary rush, only to be crushed again when the rally dissipates later in the day. For these individuals, the stock market has become more than a financial vehicle; it is an all encompassing obsession that controls all aspects of their lives. Their perspective of the stock market has become detached from reality and at time can resemble a delusion. Their portfolios no longer just signify the value of money, but rather it now also signifies how they value themselves as a person. How they do in the market becomes more of a symbolical signifier of self-worth and less about how they will meet their financial obligations. The signifier and the signified has become displaced and the stock market has now attached to an imaginary internalized scoreboard by which one’s sense of self- worth is judged. If the stocks they own are worthless then they as individuals are worthless is the kind of distorted thinking that leads to generalized despair. The psychological pain associated with this disorder can have long term psychological effects. Like most depressive disorders, it can lead to symptoms such as gastrointestinal distress, back or neck pain, insomnia, change in appetite, decrease in libido, poor concentration and even suicidal ideations. It can destroy families and careers. To ask for help is not easy for a person plagued by hopelessness and low self-esteem. However, it is essential for a person suffering from these issues to seek professional treatment and learn more adaptive ways of being. Nobody likes losing money, but cycles of severe emotional ups and downs are harmful both to one’s pocketbook and long term health. The content of this blog was recently featured in Barron's Magazine as well as published in the CT Post. www.barrons.com/articles/coronnavirus-stocks-plunge-affecting-mood-dow-affective-disorder-51584543539 www.ctpost.com/opinion/article/Opinion-Steer-clear-of-Dow-Affective-Disorder-15139793.php Dr. Klein is a clinical psychologist who practices in Fairfield and Westport CT. In addition to being a psychologist, he is also an executive coach who specializes in working with people in the finance industry. From an early age we learn to be silent. Embedded deep in our collective thoughts are proverbial beliefs such as “Children should be seen and not heard” and ‘If you have nothing good to say, then say nothing at all.” This “looking away” attitude of society has resulted in generations of adults who suffer the pain of silence -- the pain associated with being a victim of childhood abuse. How can a child, who must be dependent upon adults for nurturance and guidance, accept the terrible reality that his or her parental figures are non-trustworthy, out of control and capable of harmful abuse? How can such a child, whose basic trust and sense of self was violated, learn to trust another individual or allow for an intimate and bonding relationship? As a means of survival, victims of childhood abuse learn, early on in life, coping strategies to defend against thoughts and feelings to painful and frightening to put into words. While these defense mechanisms serve important functions at the time of the abuse, as the child psychologically develops they tend to hinder adaptation to adulthood. The traits and behaviors that were at one time beneficial in terms of helping the child survive an abusive situation become maladaptive when applied to more appropriate relationships. Healthy relationships rely upon basic trust and intimacy – two characteristics survivors of abuse tend to lack. The adult survivor relives the past in the present as if the environment they currently occupy is as dangerous, unpredictable and uncontrollable as their childhood realities. As a result, many survivors tend to be non-trusting, guarded, avoidant of intimacy and hyper vigilant. The three coping mechanisms most widely used by adult survivors to defend against painful and intruding thoughts and feelings are repressions, denial and dissociation. Many adults who have been abused as children are unaware of their own victimizations. They are unable to remember, at least on a cognitive level, their past history of abuse. By repressing these traumatic memories, the individual tempts to go on with life as if the abuse had never happened. “What I don’t know can’t hurt them” is the faulty premise upon which this defense mechanism rests. Repression, however, can only go so far. The more the individual attempts to push these negative thoughts and feelings out of mind, the more they can return in the form of flashbacks, nightmares and even psychosomatic symptoms. For example, repressed anger may result in tension headaches, fear of abandonment can manifest as gastro-intestinal problems, and feelings of guilt can appear as back or should trouble, not to mention the array of sexual, dysfunctions, eating disorders, addictions or characterological traits that can signify some form of unresolved issue related to the abuse. Victims tend to distort the facts surrounding the abuse. They deny their victimizations. They believe they desired, deserved, or willingly participated in the abuse. Many abusers threatened their victims into secrecy, leaving them to carry these concealed burdens well into adulthood. Certain victims blame themselves for the abuse as a means of gaining mastery over the abusive situation. “If I am responsible for the abuse, then I am also capable of controlling and possibly preventing the abuse.” Other victims blame themselves for the abuse because they confuse their age appropriate need for affections with abuse they received. “I am to blame because I wanted my father to come into my bedroom and cuddle.” Victims, who blame themselves for the abuse, tend to suffer from excessive guilt, depression, low self-esteem and self-defeating thoughts and behaviors, including suicidal thoughts and gestures. Dissociation in another coping strategy abuse victims use to defend against painful thoughts and feelings. When adult survivors are confronted with situations or events that symbolically remind them of the childhood abuse, they defend against these intruding recollections by either temporarily losing touch with reality or numbing their bodies so they don’t experience the pain associated with the abuse. Like a circuit breaker, dissociation shuts down a person’s cognitive and emotional processes in order to prevent an overload of painful stimuli. Dissociation, however, is only a temporary solution; it does not resolve the underlying issues that are triggering the problem. The moment the individual is confronted with internal or external stimuli that bring forth painful recollections, the maladaptive mechanisms arise and prevent the person once again from performing everyday functions. It is difficult for an abuse victim to seek professional psychological help. They are caught in a vicious circle of maladaptive defenses. To break the silence, develop trust and intimacy with a therapist, and begin to work through one’s pain is a frightening, but much needed process. For the adult survivor of childhood abuse, what is most frightening about the therapeutic process is its demand for verbal communication and intimacy. Many victims are unaware of their past history of abuse or find it too difficult to speak openly about their painful memories, especially to a therapist. Victims of abuse are conflicted about how they should relate to a therapist. They desire their therapist’s understanding and care, but fear if they let down their defenses they might become vulnerable once again to possible abuse. Childhood abuse rarely appears as the presenting problem. To diagnose a victim of abuse, the therapist must learn to read between the lines of what the person is saying or even not saying. It is within the silence that victims express their suffering and need for help. The abuse victim communicates less with speech, and more with the symbolic language of the body. There they sit facing the therapist, scared, frightened, hyper vigilant, numb, looking away from the therapist’s eyes in order to avoid what they perceive as their therapists’ piercing and critical gaze. As a perceived parental figure, therapists can easily become screens for the victim’s projections. The individual may experience the therapist as if he or she is an abuser and the therapeutic session an abusive situation. If this occurs, the conflicts and struggles the adult had as a child may be acted out within the realm of the therapeutic relationship. It is understandable why even a seasoned therapist might be disturbed by the victim’s inappropriate and situationally dystonic behaviors and actions. To cope with their own level of anxiety, some therapists might choose to relate to the patient in a defensive manner. The most common form of defense used by therapists to create distance between themselves and the acting out patient is the diagnostic procedure. By labeling a person with a diagnosis, the patient as subject is transformed into an object that can then be defined, manipulated and controlled. Because of their hyper vigilance, victims are sensitive to how others perceive them. If they feel the therapist is relating to them as an object rather than as a fellow subject, their acting out tendencies will escalate. The feeling of being objectified by the therapist will serve as a catalyst for the victim to re-experience and reenact the past abusive situation within the present therapeutic relationship. In other words, the defensive therapist will be perceived by the victim as being manipulative and controlling and as a result will react in a defense fashion against what they perceive to be a threat. The goal of treatment is not for the therapist to diagnose the victim, but rather for the victim to begin to learn how to identify and understand their patterns of thoughts, emotions and behaviors. By organizing their experiences into language, their victim will develop the psychological distance and personal integrity required to gain a sense of mastery and control. Over and against the victim’s negative projections, the therapist must relate to the victim with unconditional compassion and support. For it only by developing a safe and highly structured milieu that the victim will be able to let down his or her defenses and begin to work through the issues related to the abuse. It is understandable why the victim’s defense mechanisms might be interpreted by both the therapist and patient as maladaptive character traits. No one would dispute the negative effects these defense mechanisms have in terms of sabotaging and resisting the therapeutic process. However, to continue to view the victim’s defense mechanisms as a form of “resistance” will have a negative effect upon treatment. To critically confront the defenses can make the victim feel as defective and helpless as he or she felt at the time of the abuse. By recontexualizing these defenses mechanisms, from within the horizon of a developmental/ historical perspective, the victim will begin to realize the important role these personality traits played in terms of their survival. Defense mechanisms are, in fact, coping strategies that, in the past, helped the victim adapt to a maladaptive environment. By reinterpreting these defense mechanisms as coping strategies, the patient will begin to develop more positive self-image and begin to fell more integrated and in control. In time, they will realize that these maladaptive defenses mechanisms are no longer appropriate or needed. In addition to basic trust, self doubt is a problem that also plagues victims of childhood abuse. The victim does not trust his or her own thoughts and perceptions – especially past memories associated with the abuse. In fact, many victims are unsure if their memories are fantasy or reality. To help the victim overcome self-doubt, it is important for the therapist to validate his or her memories. What matters is not the historical facticity of the memories, but rather what psychological significance these memories have in terms of the person’s current experience. To accomplish this goal, the therapist, must keep in mind that the victim’s recollections of the past are based upon a child’s perspective – a viewpoint that is very different from how we as adults perceive ourselves, others and the world. For example, children tend to perceive adults as being bigger than life and also do not have a proper understanding of sexuality, aggression, or even a clear demarcation of self and other. From this vantage point, it is understandable why the victim’s memories might have a limited or distorted child-like quality to their narrative. Working through the defenses, learning to trust oneself and the therapist, reconnecting thoughts with feelings, and beginning to integrate the past with the present is both a frightening and exciting process. What is most frightening about the process is that it requires the subject to face the unknown, What is most rewarding about the process is that if offers the subject the freedom for personal expansion and growth. Dr. Klein is a clinical psychologist who practices in Fairfield and Westport CT. He specializes in the treatment of trauma, Post Traumatic Stress Disorders (PTSD) and adults survivors of emotional, physical and sexual childhood abuse.  Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an understanding of ourselves. Carl Jung Couples therapy is more complex than individual psychotherapy. In individual therapy you are working with one person. In couples therapy you are dealing with a minimum of two. Not only are there twice as many people in the room, but each individual brings his or her own set of psychological issues to the relationship. These psychological issues are not static, but rather are dynamic and intertwine between the couple in a myriad of complex configurations and interpersonal entanglements. Relationships can take on an ominous life of its own. When left unmanaged, it can throw couples into a whirlwind of interpersonal conflict and distress. Many couples become overcome by the negative patterns of their relationship. They feel beaten down and hopeless — victimized by how the dynamics of the relationship brings out the worst in each other. It is difficult to grasp how two individuals who at one point in time were in love now feel only contempt toward each other. How attraction can transform into repulsion so quickly is beyond all that seems rational. What complicates couples therapy even more is how each person in the relationships carries within him or herself a vast array of influential voices that have been incorporated into their own sense of self. These voices shapes the ways each partner interacts with the other. Voices from the past, present and even future can be heard within the couple’s narrative — learned beliefs, views, even politics of parents, grandparents, siblings, children, previous relationships, colleagues or friends. In some ways couples counseling is more like group therapy than individual counseling. To be successful, the psychologist must listen, comprehend, and map out all that is being said within, outside and between the two partners. It is the psychologist’s job to start the initial couples counseling sessions with a comprehensive psychosocial assessment. This is necessary in order to learn all that is being said and not said by each participant, who is being influenced by who, and how all these different voices interact and affect the dynamics of the relationship. Couples counseling can sometimes feel like a tennis match. Couples arguing back and forth, volleying for their point of view. A therapist, however, is not a referee. It is not the job of the psychologist to determine who is right or wrong or resolve a dispute by compromise. Conflict resolution is the technique used in mediation where an arbiter assists the couple to negotiate the terms of a settlement. A settlement is something that is acceptable when you are getting a divorce, not when you are planning to stay together. To settle and sacrifice your needs for the sake of the relationship can only lead to further resentment, conflict and contempt. It is counterproductive. To stick with the tennis analogy, couples counseling does not lead to “Love” just because the participants both agree to being “at fault.” Taking sides in couples counseling is a big mistake. What is important in couples counseling is for the psychologist to assist both partners to develop the ego strength to see outside their own personal assumptions and begin to understand the perspective of the other and how it relates to the dynamics of the relationship. A seasoned therapist knows the focus in working with a couple must be on insight and transformation, not on who is right or wrong. I help couples pinpoint and understand the sources of their conflicts. I will work with you to achieve a better understanding of the external influences and family dynamics that play a role in shaping your relationship and cause dysfunctional interactions. I will assist you in developing new strategies to solidify your relationship and regain trust and intimacy. The work will include learning how to openly communicate, problem solve and develop new productive ways to discuss, understand and accept individual differences. The goal of couples therapy is to learn to see your significant other in a new light, based upon insight and knowledge and not the blind subconscious forces we sometimes mistake for attraction and love. Dr. Martin Klein is a clinical psychologist who practices in Westport and Fairfield CT. He specializes in couples therapy and marital counseling. Westport marital therapist Fairfield marital therapist  Divorce is a life-altering event that can leave a profound impact on one’s mental and emotional well-being. Divorce unleashes a whirlwind of emotions, ranging from grief and anger to guilt and anxiety. At the beginning of the process, individuals may experience shock and denial, unable to come to terms with the reality of their failed marriage. As the divorce proceedings unfold, these emotions can intensify and transform, creating a roller coaster of feelings that can be overwhelming. One of the primary sources of psychological stress during divorce is the uncertainty about the future. Questions about where you’ll live, how you’ll support yourself, and what the relationship will be like with your children can weigh heavily on your mind. This fear of the unknown can lead to anxiety and sleepless nights. Marriage often becomes a core part of one’s identity. The process of divorce can result in a profound loss of identity, leaving individuals struggling to define themselves outside of the relationship. This loss of self can trigger feelings of worthlessness and lead to a deep sense of emptiness. For parents, the stress of divorce is compounded by concerns about how it will affect their children. The guilt of potentially disrupting their children’s lives can be emotionally devastating. Balancing the needs of children with the need to move on can create an intense internal conflict. Divorce can carry a social stigma that leads to feelings of shame and isolation. Friends and family may not always be supportive, and individuals may withdraw from their social circles to avoid judgment. This isolation can exacerbate feelings of loneliness and despair. The financial implications of divorce can be substantial, causing additional stress. Individuals may worry about their financial security, especially if they were financially dependent on their spouse. Navigating property division and spousal support can be emotionally draining. While divorce is undoubtedly challenging, there are healthy ways to cope with the psychological stress:

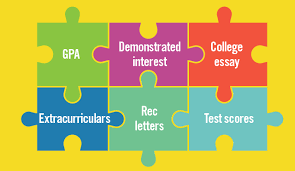

Dr. Klein is a clinical psychologist who specializes in working with individuals and couples going through separations and divorce.  To many parents a liberal arts education is no longer considered a realistic option for their children. Successful parents want successful children and as such expect them to go to highly competitive schools and study subjects deemed necessary to accelerate economic advancement. The external pressures to get into a competitive school, however, can be overwhelming to a child. Admission into a “good school” has become harder and more complicated. The world of higher education has changed dramatically over the past decade. Being a good student is no longer enough. In addition to good grades and high test scores, you now need to demonstrate that you participate in sports, extra curricula activities, do volunteer work and have completed several advanced placement courses. Even the college essay has become a monumental task, requiring professional assistance. In the “old” days students would apply to a handful of schools but now with the advent of the common application, a high school student can now send applications to 900 different colleges with a single click of a mouse. The common application has increased the pool of applicants at each college significantly, resulting is much greater competition. The college application process has become so complicated that it requires sophisticated strategies and the aid of a dedicated college coach with a specialized software program to develop a personalized strategic plan. Do you apply early decision, early admission, regular admission, how may schools should you apply to, how many safety schools, how many should be reach schools? You can now sit in front of a computer program and see how your child statistically stacks up to past applicants who applied to each respective school based upon grades, test scores etc. The severity of competition is even more intense for those kids who live in highly educated and affluent areas. It is difficult for a child to stand out from their peers when they live in a town where their cohorts all have grades and test scores two standard deviations above the norm. Being from a northeast suburb can also be a disadvantage when applying to colleges that desire student bodies that are geographically, ethnically and economically diverse. While many students are academically strong, some lack the emotional aptitude required to handle the intensity of the application process. The pressure from parents, peers and one’s self can be overwhelming to the child. Many kids I see in my practice suffer from low self-esteem. They fear that if they don’t get into a good school they will let down their parent or perhaps be ostracized by their peers. Going to classes each day, while your classmates flaunt their early admission acceptances on Facebook or by wearing collegial emblems on their clothing can bring up feelings of inadequacy. Overwhelmed by all this pressure, it is understandable why a senior in high school might become overridden with anxiety and exhibit symptoms such as an inability to relax, always feeling on edge, irrational fears of impending doom, restlessness, feeling tense and having difficulty concentrating. Sometimes general anxiety can manifest somatically as stomach pain, panic attacks, muscular tension, headaches or insomnia. Some kids try to overcome their fears by irrational thoughts or ritualistic behaviors. They become obsessed with the college application process and cannot think of anything else. They cannot control these intrusive thoughts and they find it difficult to relax or even perform chores. In many instances, the child’s academic performance begins to deteriorate due to an inability to focus. Some kids develop compulsive behaviors as a means of avoiding these negative thoughts. They watch television excessively, play endless video games, constantly surfing the internet, spend significant amounts of time on social media, or even watch hours of pornography. Many even turn to alcohol and drugs for temporary relief. High school students can also be plagued by depression. In children, depression can manifest in many different ways. For example, some kids with depression might feel sad, hopeless, have difficulty concentrating, sleep poorly, have little appetite or an inability to experience pleasure. Others can experience depression in how they interact with others. They can be socially withdrawn, avoid responsibilities, procrastinate, or become emotionally sensitive. Some kids manifest their depression by exhibiting oppositional behaviors. They can become agitated, aggressive or even antisocial. Kids who have been well behaved can suddenly become deviant. It is common for students to feel embarrassed, ashamed, or over ridden with guilt about failing to live up to expectations. Many kids, as well as their parents, have separation anxiety and get nervous even with the idea of the child going off to college is mentioned. Many high school students feel alone and isolated in their suffering. They feel like they have no one to turn to who can understand their pain and give unbiased advice. They fear rejection by their parents, teachers and friends. Kids are often relieved to finally have someone who they can talk to confidentially, in an open manner, without the fear of criticism or judgement. Many can finally admit that the issues that are bothering them have been around for a long time. They can explore their family dynamics in a safe environment and begin work through the age-specific developmental issues of separation and self-identity, which can be overwhelming and confusing to a child at this age. Who are they? What do they they want to be when they grow up? How do they get their needs met? How do they become that person they want to be? What is the path they should pursue that will make them happy? And most importantly, what college do they want to go to and what subjects should they study? Surprisingly some kids feel a sense of relief when they discover they will be going to one of their safety schools. Safety, especially to a child, is not always a bad thing, and often times a welcomed surprise. Dr. Martin Klein Is a clinical psychologist who practices in Fairfield, Westport and Stamford CT. During these stressful times, he is currently offering video conferencing to all students and families across the state of Connecticut. He specializes in working with high school students who struggle with issues of anxiety, stress, depression, low self-esteem and addictions. He works closely with students and their families who are going through the college application process. From an early age we are taught to fear the possibility of unwanted pregnancy. Our parents, teachers and clergy have educated us about the importance of protected sex and even abstinence.