|

Major Depressive Disorder (MDD) Major depression is a disabling condition that can last for long periods of time. Without treatment, a major depressive episode can last months, years and even a lifetime. While the condition can worsen during the holiday season or winter months, it is most often triggered by a personal loss or negative situational event. MDD can run in families. In many cases, the mood disorder can be biologically or socially based or a combination of both. How one was raised as a child is an important contributing factor in MDD. Individuals who suffer from dysthymia, a low-grade continuous depression, are most vulnerable to bouts of major depressive episodes. People who have never experienced major depression might not understand the depth or severity of the syndrome. There can be nothing more frustrating to a depressed person than someone telling them they should just “snap out of it,” “you have no reason to be unhappy,” or “you just need to pull yourself up with your own boot straps.” Major depression is not something that tends to go away on its own without professional intervention. When you are clinically depressed you can feel totally helpless and have little hope that you will ever feel better. You tend to forget what it feels like not to be depressed. If someone tries to remind you of past times when you were happy, you quickly view their opinions as ill informed and agitating. You feel depressed and exhausted all the time. Your mind is occupied with negative obsessions, self-deprecating thoughts, and low self-esteem. There is a melancholia to your mood. You might feel sad, overwhelmed and psychologically paralyzed. You might feel that your life has no purpose or meaning. You have a hard time falling asleep and if you do fall asleep you tend to wake in the middle of the night worried and frightened . You cannot shut off your mind. You thoughts are racing with irrational fears and anxiety provoking self doubts. When you are depressed you can become easily agitated and angry. Even the smallest gesture by another person can be misinterpreted and set off a tirade. Some people become so frustrated that their anger rises to the level of rage, whereby they become capable when provoked of doing bodily harm to themselves or others. Depression can cause difficulties in focusing and concentration as well as deficits in abstract reasoning and memory. Being productive at school, work or at home can be difficult, if not impossible. In severe cases, a person might not have enough energy to get out of bed, care about their appearance or perform basic activities of daily living. Suicidal thoughts or actual attempts are not out of the question. If you or someone you know suffers from clinical depression, it is important that seek professional help as soon as possible. Clinical psychologist are trained in the diagnosis and treatment of mood disorders. Depression is treatable. Utilizing a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), insight oriented psychotherapy and sometimes medication, the clinical psychologist can come up with an action plan to alleviate your symptoms and make changes to how you think, behave, relate to others, and experience yourself and the world around you. Dr. Martin Klein is a clinical psychologist who specializes in the treatment of depression. He has offices in Westport and Branford CT.

1 Comment

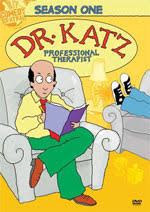

A man says to his wife: "Listen honey, whoever dies first, I want to make sure it is okay that I remarry." Sigmund Freud Jerry Seinfield on Choosing a Psychotherapist www.youtube.com/watch?v=fG7ymv0ptLo Bob Newhart on Brief Focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy www.youtube.com/watch?v=4BjKS1-vjPs Woody Allen on Long Term Psychoanalysis www.youtube.com/watch?v=ocMOJXkz9eI Kelsey Grammer (Frasier) on Hypnosis www.youtube.com/watch?v=LbyzC07HLow Ray Ramano on Martial and Family Issues www.youtube.com/watch?v=CHS-tXxHl1w Robin Williams on Alcohol Dependence www.youtube.com/watch?v=uLtPp_xIpC4 Jackie Mason on Self-Identity and Psychiatry www.youtube.com/watch?v=n3ZDslOxPhI Stephen Wright on Early Childhood Memories www.youtube.com/watch?v=MdDEz1aJSAc Jim Parsons (Sheldon) on Facing Your Fears www.youtube.com/watch?v=QV6DpJKW6a0 Bill Murray on Hypochondriasis www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bYO-mm_MvMhttps://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1bYO-mm_MvM Richard Lewis on Psychotherapy and Termination www.cc.com/video-clips/9auw7c/stand-up-richard-lewis--out-of-therapy A psychiatric diagnosis is a cluster of psychological and behavioral conditions as defined by the American Psychiatric Association's Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Over the years, there has been numerous revisions of this manual. With each revision, there tends to be significant changes to the different menus of diagnoses and how each diagnosis is defined. For example, in the most current manual the diagnosis of "Asperger's disorder" has been removed and is now considered as a part of the class of "Autistic Spectrum disorders." In one of the earliest manuals there was diagnoses termed "Neurotic disorder." The term " neurosis" is no longer considered a proper diagnostic disorder and it has been eliminated from the manual. So what happens to an individual who has a diagnosis that the American Psychiatric Association decides no longer should exist? What happens to the child I work with who has been labelled "Aspergers" for the past several years and now has a new diagnosis? What about poor Woody Allen? If he can no longer be considered a "Neurotic" can he still make movies? As several of the great existential thinkers have pointed out, psychiatric diagnoses are not objective disorders, but rather are social constructs that change over time (i.e., Szasz, Lang, Foucault). When I worked in a psychiatric hospital 25 years ago, the most popular diagnosis was "Schizoaffective Disorder." What did that diagnosis mean? Basically the person was having problems with his or her thought process (schizo) and well as his or her mood (affective). I remember doing an inpatient group with 10 individuals, all diagnosed with "Schizoffective Disorder". All of the people in group did have something in common -- they were not thinking clearly and had mood issues. However, the similarities stopped there. Each person was unique. Each had a different reason for being in the hospital as well as different backgrounds and issues. In fact, at the time, I remember thinking to myself, I would not be thinking clearly or be in a very good mood if I was hospitalized in a psychiatric hospital against my will either. Today the new popular diagnosis is "Bipolar." Almost everyone coming out of a psychiatric hospital comes out with a diagnosis of "Bipolar." If you are not thinking clearly or having mood issue you are now identified with this now popular disorder. The other widely popular modern day diagnosis is "Attention Deficit Disorder (ADHD)". So many kids these days are being put on speed to improve their attention. Does speed improve one's attention, most definitely. Should all children who have focusing issue be diagnosed with "ADHD" and put on speed? I personally feel it is a significant social problem. Psychiatric diagnoses are clusters of symptoms. They change over time dependent upon what is popular in the current culture; and more specifically the psychiatric community. Diagnoses are tools people in the field of mental health use to describe a cluster of symptoms and behaviors. There are many theories as to what causes a person to be and act a certain way, but these theories also change over time and are historically dependent on the culture and trends in the psychiatric field. So what is my point? You should not define yourself by your psychiatric diagnosis. Diagnoses are helpful in understanding psychological symptoms and patterns of behavior. They can be a great tool for the clinician or the psychiatrist in determining the best treatment or medication. A person diagnosed as "Bipolar" is an individual who is possibly struggling with his or thought process or mood. Therapy and medication can help. However, having these cluster of symptoms, thought or behavioral patterns, do not define who you are as an individual with unique personal issues and struggles. Dr. Klein is a clinical psychologist who practices in Westport CT. He specializes in psychiatric assessment and psychological treatment from a humanistic existential orientation. Copyright April 2016, Martin Klein, Ph.D. I often see patients who want to know why they do certain activities that on the surface do not seem to make sense. From a practical perspective, these odd behaviors seem out of character or of a compulsive nature. "I cannot stop doing the action, even though it seems irrational and a waste of time." In the therapeutic process, the reasons whey we do certain things or act out in a particular fashion is not always transparent and may take awhile to figure out. It is a wonderful part of the psychology process -- an "aha moment" -- when the person and his or her psychologist discovers the meaning of an action. Many people want a quick fix -- they want the negative behavior or the painful symptom to go away quickly and effortlessly. In some cases this makes sense. But sometimes, it does not. To use an analogy, does it make sense to turn off the fire alarm while there still is a fire burning or a lack of understanding as to the cause of the fire? I once had a patient with a unique presenting problem. For dinner he would eat the same thing every night -- steak, string beans and creamy mashed potatoes. He would eat the steak first, then the string beans and then finally the creamy mashed potatoes. He would always save the creamy mashed potatoes for last, it was his favorite. However, each night, by the time he finished the steak and string beans, the creamy mashed potatoes were cold. That is right, his presenting problem was cold creamy mashed potatoes. Now if I was a "practical type of psychotherapist", the fix would be easy -- after you finish the steak and string beans, stick the creamy mash potatoes in the microwave and warm them up. But to follow-up with my fire analogy, it is my view that such an action would be like shutting off the fire alarm and not dealing with the real burning issue. For this gentleman, this compulsive pattern was symbolic of a greater issue that in fact affected the very core of how he lived his life. I would call it the "you cannot win syndrome." In his life, he felt like he works very hard, but the reward that he expects for his hard work never comes or when it does finally come, it is cold lumpy and does not taste good. The creamy mash potatoes was symbolic of personal freedom -- the "easy life" -- the effortless melting in your mouth -- an experience this person never seemed to get to. As many of the great existential thinkers have taught us, human beings are symbolic creatures and think, act and behave with in the realm of the symbolic (Freud, Jung, Eliade, Ricouer). Many of our activities have deep symbolic significance. While these symbolic actions resonates with our sense of well being, their meanings tend to stay hidden. The most obviously place where the symbolic realm can be most seen is in the world of games. What is the attraction of tennis? Is tennis a working through of some deeper issue? I often talk about tennis when I am doing marital therapy. Isn't tennis a game about relationships -- who is left with the ball in their court --who is at fault? -- are we equally at fault? -- ah then we have "love." Why do we love to watch football so much -- the great American obsession? What is the symbolic meaning of the game? What is the goal of football, if not to get the ball, which is shaped like a egg -- the symbol of perfection -- to the goal post without it falling and cracking. Why do they pile on the player who is already down with the ball? Why is it so important to make sure the other team does not get back up? Why are our kids so addicted to video games? Are the themes of these games resonating with our children's needs or desires on a symbolic level? In 1980s, when I was working as a school psychologist, I was fascinated with adolescents' obsession with "Pac-Man." This was before computers, and kids would spend endless hours after school at the arcades. In 1984, I published an article entitled "The Bite of Pac-man" where I explored the symbolic allure of the game. Why did the theme of the "Pac-Man"game resonate so much with adolescents? As I discussed in the article " The themes and strategies of the game perfectly accommodate the adolescent's relation to the world. The Pac-man creature, which the player controls and symbolically becomes, is all mouth and is referred to as "Jaws." "Jaws" spends his time and energy running from the engulfing monsters. There are four different types of monsters, each with its own personality: "Shadow" always follows you; "Bashful" will run away when you turn around; "Ambition" is always willing to attack you; and "Speedy" is fast and will run over you.... If the player engulfs enough monsters before they engulf him, he becomes a winner." While the game of "Pac-Man" might be a safe place to work out issues of separation and individuation, it is still a game -- a feel good fantasy -- not an achievement of personal maturity and a true reflection of one's ability to survive in the world. What are some of the symbolic things you do or participate in as you live your life? Do you have activities or compulsions that you are addicted to and are not sure why? Symbolism and everyday actions, it is something to think about. Dr. Klein is a clinical psychologist who practices in Westport CT. He specializes in life transitions, relationship issues, identity, personal growth and self understanding. He is trained in both clinical psychology and existential philosophy. The Affordable Care Act, more commonly known as Obamacare, is a perverse twist on the Robin Hood tale. Rather than steal from the rich, Obamacare has taken from the middle class. Prior to ACA, the self-employed middle class had many options for comprehensive insurance. They were largely able to afford their premiums and deductibles, and out of pocket costs were manageable. Most importantly, they were free to choose their own doctors and hospitals from a nationwide provider network. To use my family as an example, four years ago I had a PPO plan that cost around $16,000 a year and had a maximum out of pocket expense of $2,500. The plan offered a national network and I was able to go to any doctor or hospital. Today you cannot buy such a plan at any price. The option that comes closest to the plan we had is a “Gold” HMO policy, with a premium of around $44,000 with a $9,600 out-of-pocket maximum. For the middle class, such a policy is financially prohibitive. Over the past four years, medical costs for the self-employed have gone up over 300 percent and the coverage of the plans has deteriorated. For a middle class family of four, making around $98,000 there are no subsidies. You have two options — buy what amounts to an expensive catastrophic policy with constricted benefits, or pay the tax penalty, be uninsured, and hope for the best. And while many middle class families — whether they qualify for subsidies or not — may be able to afford their premiums, they may not be able to afford their deductibles. How many of us can afford to pay a $13,500 bill that comes in the mail? In effect, they will be able to afford their policies but be unable to utilize them. On the individual market, there are only two insurance companies to choose from — Anthem or Connecticare. Connecticare’s rates are slightly less expensive. But for the most part, the plans are similar. There are only two places where you can buy insurance — on the exchange or off the exchange. The exchange plans tend to be significantly cheaper than the off-exchange plans. For example, a Connecticare plan is about 35 to 40 percent cheaper on the exchange than on off the exchange. From a cost perspective, the exchange plans make the most sense. However, from a network perspective, the plans on the exchanges are extremely limited in terms of the size and scope of their networks. On the exchange, the provider network is restricted to the state of Connecticut, and even then many of the best doctors and hospital programs in the state are not on the panels. While many of the exchange plans offer out-of-network coverage, this benefit has even higher deductibles, and poor reimbursement rates – often less than half of the customary rate. So if you choose to go to an out-of-network provider, your out-of-pocket costs can be through the roof. In terms of coverage, the off-exchange plans are better, but not much better. Off the exchange, your network will be larger and you will have a better chance of finding a provider you like or one that is taking new patients. Some plans even let you see providers in some of the surrounding areas beyond the borders of Connecticut. However, even if you go with an off-exchange plan, the networks are still limited and are not national in scope. They do not compare to an employer-sponsored policy. Once you’ve decided whether you want to buy a plan on or off the exchange, the next decision, is the type of plan — a high deductible or low deductible plan. There are three sets of numbers you have to look at to compare plans: premiums; deductibles; and maximum out-of-pocket costs. For the most part, it all boils down to a simple equation: the higher the premium, the less the out-of-pocket expense; the lower the premium, the more the out-of-pocket cost. From a financial perspective, I believe it makes sense to go with the lowest premiums and the highest out-of-pocket cost. If you have few health care needs during the contract year, you will have to spend little out of pocket towards your deductible. So whether you pay the actual amount of your deductible is not necessarily a given. If you are fortunate and do not meet your $13,500 deductible, you end up saving money with the lower premium plans (lower premiums in my family’s case is $28,500 a year, with a $13,200 out of pocket maximum). I think you have nothing to lose by taking the lower premium plan, and much to save. But some people, from a psychological perspective, prefer to pay higher premiums and then not have to worry about having to pay for services rendered. But whichever route you go, maximum out-of-pocket costs, (premiums, deductible, out-of-pocket max) for all the plans ends up being about the same. In summary, if you are OK with only going to a Connecticut hospital, and most of your doctors are on the exchange network, the exchange plan makes sense. If you might want to go to a New York City hospital, there is a strong possibility that there can be a significant out-of-pocket expense. If you want to go to a provider or facility in Ohio or California, this is no longer possible, no matter which plan you choose, except in the case of emergencies. For the behavioral healthcare provider, the ACA has been problematic as well. While they have raised premiums, they have not raised what they pay providers in over a decade. In some cases, they have actually decreased their allowable rates by over 50 percent. Member cost have gone up over 300 percent, provider reimbursements have stagnated or have gone down – yet the stocks of these managed care companies have gone up over 400 percent in the past four years. No surprise there. At risk of being labeled the “L” word, I believe that everyone — middle class included — should be entitled to good health coverage. Martin H. Klein, Ph.D. is a licensed clinical psychologist practicing in Westport and Fairfield CT. This article was originally published in the CTMirror. Click below to see link to original article Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD) is a type of depression that is related to the changes in the season. Symptoms typically start out mild in the fall and gradually become more severe as the winter approaches. This syndrome is often referred to as the "winter blues” because it is triggered by the lack of day light and the cold weather. Like other forms of depression, people who have SAD can be overwhelmed with feelings of guilt, anxiety and despair. They can feel like the energy in their body has been zapped resulting in sluggishness, poor concentration and little motivation to do activities that they once found to be pleasurable. Due to intrusive negative thoughts, they can easily become agitated. This high degree of irritability can make it hard to fall asleep and stay asleep, resulting in exhaustion and mood swings. One's appetite is often affected and accompanied by either weight gain or loss. Many people who have SAD suffer from low self-esteem. Some of the factors that seem to play a role in the onset of SAD is a change in circadian rhythms. The research suggests the reduction in sunlight disrupts the body's internal clock and throws off one's sense of well-being. Not having enough sunlight can also cause of drop in serotonin, a neurotransmitter, that when lowered results in mood changes associated with depression and anxiety. The change in seasons can also disrupt the body's level of melatonin. Melatonin plays an important role in sleep patterns, affect and energy level. There are several treatment options for individuals who suffer from Seasonal Affective Disorder. It is important to discuss your symptoms with your primary care physician (PCP) to rule out the possibility of other medical conditions that can cause mood changes. If your PCP does diagnose you with SAD, he will most likely refer you to a clinical psychologist for psychotherapy to learn strategies to identify and change negative thoughts and behaviors as well as learn relaxation techniques to reduce stress, bodily tension, and elevate one's mood. Light Therapy, also called phototherapy is often utilized to treat SAD. Utilizing a special light box, a person sits in front of this special bright light for an hour each morning. The light therapy mimics the natural light that occurs in the spring and summer months and affects a change in the brain's chemicals linked to moods. Light therapy typically begins working within a few weeks and there are few negative side affects. Some people benefit from medications. Wellbutrin is an anti-depressant that is often used to treat severe cases of SAD. The medication can be taken during the SAD season, from late fall until the end of winter each year. Exercise, meditation and stress management tools can also be helpful to reduce SAD symptoms. Dr. Martin Klein is a clinical psychologist who specializes in Seasonal Affective Disorder. He has offices in Westport and Branford CT. What is Hypnosis? When you hear about hypnosis, often you might think of an ominous figure waving a pocket watch back and forth or a stage hypnotist making people do things against their free will. While these images may be popular on TV or in the movies, the type of hypnosis I am going to discuss is not used for dastardly deeds or entertainment purpose. I promise none of my patients are turned into zombies, bark like a dog or cluck like a chicken after I hypnotize them. Hypnosis is a deep relaxed state where you become open to intense focus, heightened imagination and suggestion. This hyper-attentive state is called a “trance.” Counter to what many people assume, you do not lose your free will or ability to be in control of you own wits when you are in a trance. In a trance you are fully conscious and alert. You are not asleep, but rather you are intensely focused on the subject at hand. When you are in a trance, you feel uninhibited, relaxed and tune out the worries, doubts and self–conscious thoughts that restrict your ability to be attentive and focused. Most people have experienced a trance like state. Milton Erickson, a world renowned hypnotist of the 20 century, contended that most people walk around in a trance on a daily basis. Have you ever spaced out in your car and miss your exit, day dreamed during a lecture, became so absorbed in a book or video game that you do not hear someone calling your name? Perhaps we spend more time in a trance than we would like to admit. When done properly, hypnosis can be a helpful intervention used as part of the psychotherapeutic process. Hypnosis can be combined with psychotherapy to treat an array of psychological issues related to trauma, anxiety, stress, addictions, pain and eating. The History of Hypnosis Hypnosis is not a new procedure in the world of mental health. The medical community began using hypnosis to treat psychological conditions over two hundred years ago. In the 18th century an Austrian physician, named Franz Mesmer, was the first person to utilize hypnosis to treat both medical and psychological aliments. His name is still synonymous with hypnosis. A person in a trance is sometimes referred to as being “mesmerized. ” In the 19th century, hypnosis was being used by the psychiatric community to treat psychosomatic related illness. Sigmund Freud was one of the first physicians to use hypnosis to treat patients who suffered from psychological conditions due to repressed memories. By using hypnosis, Dr. Freud was able to reduce the patient’s high level of anxiety so she could unblock and work through the past trauma that was causing her symptoms. How Does Hypnosis Affect You Physiologically? Most scientists today believe that hypnosis subdues the conscious mind so that it takes a less active role in your thought process. By calming your conscious mind, the psychologist can have greater access to your subconscious thoughts and be attuned to your deeper thoughts and emotions that affect who you are and how you think and feel. It can bring up past memories and experiences that you have either repressed because they were too painful or anxiety provoking. There is ample evidence in the literature that hypnosis does in fact make significant physiological changes to one’s body and state of mind. Like many forms of deep relaxation, research has shown that hypnosis lowers heart rate and slow down respiration. Utilizing electroencephalographs (EEG), researchers have demonstrated when in a trance there is a boost in the lower waves associated with sleep and dreaming and a decrease in the higher frequency waves associated with full wakefulness. In addition, neurologists studying the cerebral cortex have demonstrated that hypnotized patients show a decrease in left hemisphere activities and an increase in right hemisphere activities. The left hemisphere controls logical and deductive reasoning and the right hemisphere controls the creative and imagination functions of the cerebral cortex. Can I Be Hypnotized? The literature suggests that 75 to 80 percent of the general population can be hypnotized. In my own practice, I have found most people are able to hypnotized, if they are opened to the process and do in fact want to be helped by the intervention. Motivation is an important factor in determining whether hypnosis will work. Unlike a fixed gaze induction -- the method you often see on TV -- in my Westport, CT office I do a progressive relaxation and imagery induction that gradually relaxes the patient, keeps their conscious controlling mind busy, so he or she can relax into the trance in a non-defensive manner. The progressive relaxation and imagery method works well with individuals who are anxious, and have a hard time shutting off their minds or fear losing control. It works like the magician who has the audience focus on what they are doing with their right hand to distract them from the actual trick being done with their left hand. It is my experience that even people who find it impossible to meditate are able to relax with hypnosis because their active mind are being occupied by the continuous verbal cuing of the hypnotist. In order to achieve a decrease in symptoms or a reduction in bad habits, I utilize a combination of hypnosis and behavior modification. Like cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT), the patient learns techniques to reprogram negative thoughts and behaviors while in a trance. For example, the cigarette will taste bitter or take 3 sips of cold water and you will not feel anxious when you cross the bridge. Will Hypnosis Help Me? Prior to utilizing hypnosis, it is important for the clinician to do a comprehensive psychiatric assessment to determine if the person has the mental stability and ego strength to undergo such a procedure. Hypnosis is not for everybody. Hypnosis is not for individuals who suffer from severe thought or mood disorders. If a person is not psychologically stable, hypnosis, like many forms of deep relaxation, can have negative consequences, and lead to psychotic breaks or mood instability. Hypnosis can be an excellent tool used as part of the psychotherapeutic process. I find it particularly helpful for individuals who suffer from anxiety. Many primary care physicians and psychiatrists refer their patients to me after all else have failed. Their patients tried all different types of psychotherapy and medications, but they are still anxious. In addition to general anxiety, panic attacks, phobias, obsessions and compulsions, hypnosis is an excellent tool in working with people who suffer from Post-Traumatic stress Disorder (PTSD). Hypnosis allows the psychologist to work on the traumatic issues in a safe and contained manner. By limiting the trauma work to the hypnotic session, the individuals gets to work through the trauma, while still being able to function normally when not in the doctor’s office. How Long Does Hypnosis Take to Work? I can often tell if a person will benefit from hypnosis in a couple of sessions. If the suggestions work, you should have results right away. However, hypnosis is an accumulative process and often takes numerous sessions to have a long term affect. Hypnosis alone cannot stop an addiction, eliminate an irrational fear, or modify how one thinks or behaves. Change takes insight and cognitive and behavior modification. In many cases hypnosis works best in conjunction with insight psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and/or medication management. When it comes to anxiety, learning how to relax one’s body is essential. I often tell my patients how important it is to do both aerobic exercises as well as yoga or stretching to loosen bodily tension. As part of hypnotic exercise, I relax each part of the patient’s body and can see first-hand where they hold tension in their bodies. An important component of hypnosis is self-hypnosis; learning exercises to do at home on a daily basis in order to achieve behavior modification, symptom relief and significant reduction in daily stress. I look inside myself and see my heart is black I see my red door and must have it painted black Maybe then I'll fade away and not have to face the facts It's not easy facin' up when your whole world is black The Rolling Stones The Holiday Blues The holiday season is typically a joyous time. We are often surrounded by loved ones exchanging gifts and good cheer. However, the holiday season can also be a stressful time. Shopping for gifts or sending out cards can be time-consuming and a financial strain. Many people travel to be with families, which can be tiring. Those who travel far might even suffer from jet lag. Being with one’s extended family can be emotionally draining. Dysfunctional family dynamics that have been dormant all year can rear their ugly head. Our expectations don’t always match up with the idyllic representations we see in the movies or on tv. New Years can bring up feelings of remorse and failure. To some the tinsel and bright colorful lights are nothing more than a reminder of the darkness and cold of winter that looms just below the ornaments. During the holiday season many feel isolated, alone or unhappy with their current relationships. They might hate their jobs or even be unemployed. They might be physically ill or are close to someone who is sick or even dying. As we get older, the holidays can become an annual reminder of the loved ones we have lost over the years. We are flooded with childhood memories, some good and some bad. Many of the loved ones we grew up with are no longer with us. When we gather with family and friends, we often over eat, drink too much, skip exercise routines, and don’t get enough sleep. It is common to feel exhausted and a bit grumpy around holidays. Moments of depression are not uncommon. It is easy to see how you can suffer from the holiday blues. For many getting through the holidays can be a relief. Once you get back into your daily routines, much of the holiday malaise tends to pass. You are aware that the days will get longer, there will be more daylight, temperatures will warm up, and spring will soon be in the air — and you have 365 days until your next family gathering. You begin to exercise again, eat healthy and are glad to be back to work and your daily routines. But this is not the case for everyone. Depression can drag on beyond the holidays. Some people experience bouts of depression that can last the entire winter season, and in some instances even longer. Dr. Martin Klein is a clinical psychologist who specializes in the treatment of depression. He has offices in Westport and Branford CT. I Tell It Like It Is

Expressions people use can tell you a lot about how they think, act and relate to others. One expression I often here in my work is: "I tell it like it is." On the surface, what I think the person is trying to convey is that he or she is a " straight shooter" -- honest, does not play games and only speaks the truth. But if one digs a little deeper, and explores the psychological assumptions that underlie such a statement, a more revealing meaning of how the person sees and understands his or her surroundings becomes apparent. The expression: "I tell it like it is" signifies that the person truly believes that he or she is seeing things how they really are -- i.e., objectively. Common Sense Verses Subjectivity Many people who say statements like "I tell it like it is" also believe they possess what they refer to as "common sense." They believe they are able to see things the same way other people see things who are down to earth, level headed and don't have their heads up in the clouds. But are these people actually seeing things as they truly are in an objective manner? As a psychologist, the idea that someone believes they see things "objectively" is always suspect. Can a person actually see things as they are or does each person have a particular perspective? Existential philosophers refer to the concept of perspective as "subjectivity." They often use the analogy that each individual sees the world through a tinted lens. We all know that some of those lens can be dark, others grey or red, and for the fortunate ones perhaps rosy. When I contemplate the concept of "common sense" I always think of the proverbs my parents and grandparents taught me. They spoke as if they were fundamental truths and rules to live by. However, If you analyzes these proverbs, one discovers that many of them actually contradicted each other and did not have much in common . To make my point, here is a short list of some common sense proverbs that contradict each other: He who hesitates is lost.......................................All good things come to those who wait You are never to old to learn...............................You cannot teach an old dog new tricks It is better to be safe than sorry'..........................Nothing ventured nothing gained The best things in life are free.............................There is no such thing as a free lunch Opposites attract ................................................Birds of a feather stick together Actions speak louder than words.....................The pen is mightier that the sword A rolling stone gathers no moss..................... Stop and smell the roses A penny saved is a penny earned...................Penny wise and pound foolish As you can see, the wisdom of common sense is not always consistent or objective. There are many perspectives and some of them are contradictory. When someone says "I tell it like it is" what they are really doing is telling it as they see it -- and how they see it is colored by their own subjectivity. When someone say "I have common sense" what he or she really is saying is that they believe their perspective is the right one -- the point of view that others should also take as truth. Copyright July 2016, Martin Klein, Ph.D. |

AuthorDr. Martin Klein is a clinical psychologist who practices in Westport, Stamford and Fairfield CT. He specializes in individual therapy, Couples counseling and executive coaching. |

Martin H. Klein, Ph.D., Psychologist, Westport, Fairfield, Stamford, CT, 203-915-0601, [email protected]